Editor’s Note: In January, WhyHunger staff joined a 10-day delegation coordinated by the Friends of the ATC – a solidarity network that supports the Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo (Rural Workers’ Association) Nicaragua, which brought together a diverse group of people from grassroots & social justice organizations, farmworkers from across the U.S., Canada, Germany & students from Latin America to gain firsthand knowledge of how peasants in Nicaragua have been using agroecology, food sovereignty, feminism, socialism & anti-imperialism as a foundation of the society they have been building since the Sandinista Revolution of 1979. In the blog post below, Betty Fermin, WhyHunger’s Global Movements Program Coordinator, shares her reflections and observations based on her participation in this delegation to Nicaragua.

Following on the heels of my colleague’s reflections of our trip to Nicaragua, I am still inspired after witnessing the power of agrarian reform and food sovereignty. We spent the first few days of our trip learning about the social and political context of Nicaragua and the work of the ATC. Then our large delegation was split into 4 smaller groups and we traveled into the countryside to spend time in communities that have benefitted directly from learning and organizing with the ATC.

I was a part of the delegation group in Carazo, the southwest region of the country. We began by meeting with ATC Federation Carazo leaders and then headed to the nearby Santa Teresa municipality to meet the Marlon Alvarado community. We were welcomed with a delicious lunch from the families that would be hosting us over the next couple of days. The Marlon Alvarado community is made up of the strong women that have learned through involvement with the ATC about agroecological practices, and hammock making. Men in the family who also work the land were included in those trainings. Gender equity is a clear value for this community in that the women take the lead, but the whole community works and learns together and collaborates on all aspects of life. I got to stay with the Vega family, Doña Lucila, Don Bismarck and their teenage daughter Glenda. We started our first day of learning by observing how they live on their parcel, the land they received in the 1980’s during the agrarian reform.

I was a part of the delegation group in Carazo, the southwest region of the country. We began by meeting with ATC Federation Carazo leaders and then headed to the nearby Santa Teresa municipality to meet the Marlon Alvarado community. We were welcomed with a delicious lunch from the families that would be hosting us over the next couple of days. The Marlon Alvarado community is made up of the strong women that have learned through involvement with the ATC about agroecological practices, and hammock making. Men in the family who also work the land were included in those trainings. Gender equity is a clear value for this community in that the women take the lead, but the whole community works and learns together and collaborates on all aspects of life. I got to stay with the Vega family, Doña Lucila, Don Bismarck and their teenage daughter Glenda. We started our first day of learning by observing how they live on their parcel, the land they received in the 1980’s during the agrarian reform.

From 1936 to 1979 Nicaragua was under the Somoza dictatorship, which prioritized having land privatized and held by large landowners. This resulted in an economy where rural land ownership was concentrated in the hands of relatively few Nicaraguans who exported mostly to the United States. The Sandinistas came into power in part because they offered an alternative, especially for the people living in rural areas and landless farmers. Among the vital programs the Sandinista government instituted, they established agrarian reform. This land reform policy resulted in the redistribution of land to landless peasants, cooperative farms and state-owned agricultural businesses with the goal of decreasing rural poverty and hunger. Agrarian reform in Nicaragua did not seize or take land to expand the amount of land used but worked to reallocate land that was not being used, no matter the size, whether it was abandoned or underutilized.

From 1936 to 1979 Nicaragua was under the Somoza dictatorship, which prioritized having land privatized and held by large landowners. This resulted in an economy where rural land ownership was concentrated in the hands of relatively few Nicaraguans who exported mostly to the United States. The Sandinistas came into power in part because they offered an alternative, especially for the people living in rural areas and landless farmers. Among the vital programs the Sandinista government instituted, they established agrarian reform. This land reform policy resulted in the redistribution of land to landless peasants, cooperative farms and state-owned agricultural businesses with the goal of decreasing rural poverty and hunger. Agrarian reform in Nicaragua did not seize or take land to expand the amount of land used but worked to reallocate land that was not being used, no matter the size, whether it was abandoned or underutilized.

Doña Lucila and Don Bismarck are a living example of how to benefit from the government’s ‘bono productivo’ program- a Zero Hunger program in which the government aims to improve and increase the role of women in food production by providing support to raise pigs in “deep beds” as well as add chickens and cows to their farming activities. When it comes to the pigs, the raised beds do not smell, and the animals are treated humanely. They are fed with rice husks, a by-product of the rice processed by farmers at the local rice mill. I was struck how nothing went to waste, as I watched farmers go to this mill to separate the husks from the rice they grow to feed themselves and their animals. In their yard, they also have dozens of fruit trees. Watching all this unfold, I thought to myself “Now, this is food sovereignty in action.”

Doña Lucila and Don Bismarck are a living example of how to benefit from the government’s ‘bono productivo’ program- a Zero Hunger program in which the government aims to improve and increase the role of women in food production by providing support to raise pigs in “deep beds” as well as add chickens and cows to their farming activities. When it comes to the pigs, the raised beds do not smell, and the animals are treated humanely. They are fed with rice husks, a by-product of the rice processed by farmers at the local rice mill. I was struck how nothing went to waste, as I watched farmers go to this mill to separate the husks from the rice they grow to feed themselves and their animals. In their yard, they also have dozens of fruit trees. Watching all this unfold, I thought to myself “Now, this is food sovereignty in action.”

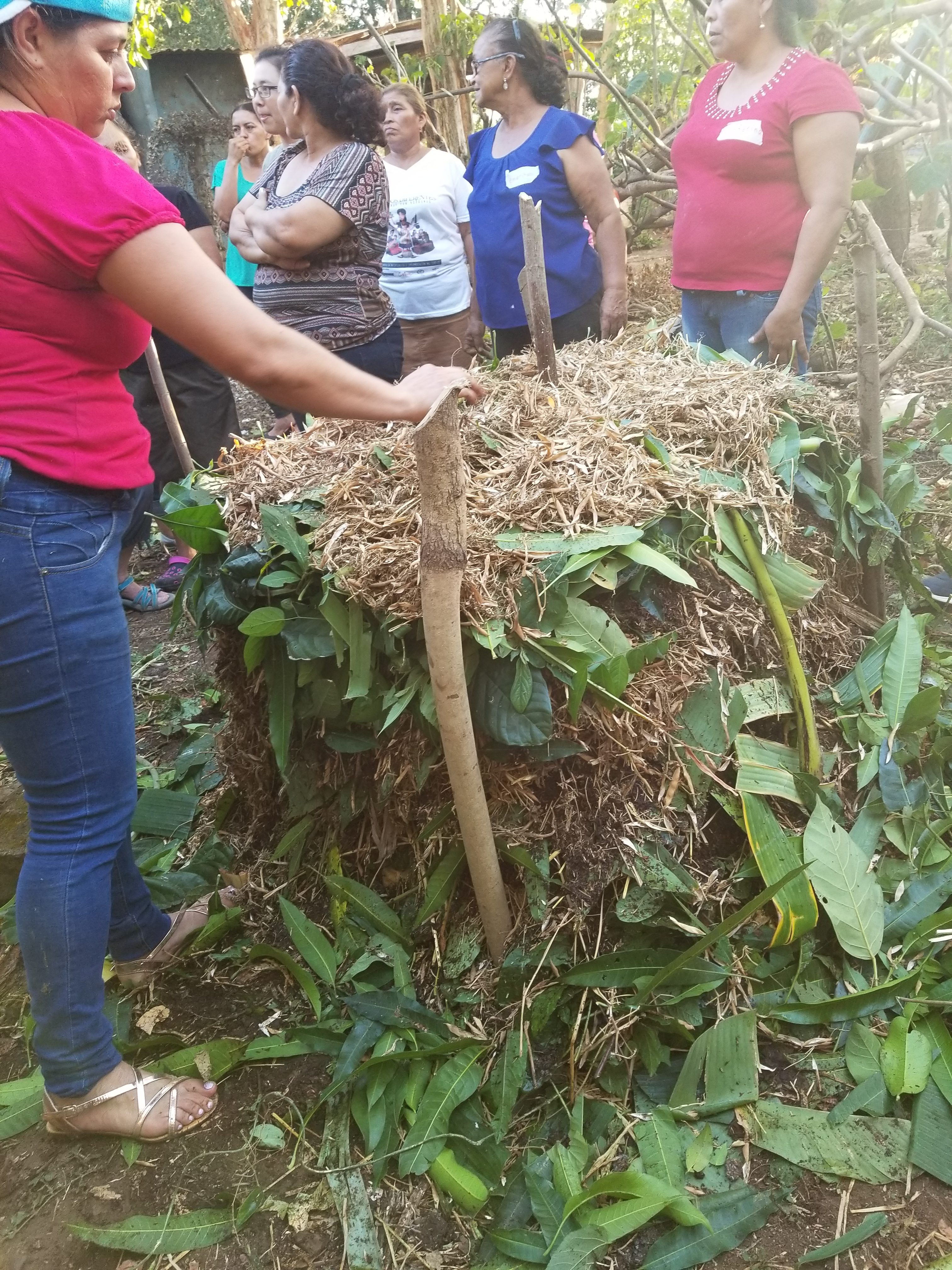

Something that was clear when the group of women in the community began to share their knowledge with us is how organized they are and how they share amongst each other. Our small delegation — made up of people from the U.S., agroecology students from Nicaragua, the group of women and their husbands from the community — spent the first afternoon learning about the raised beds and making compost. It was a great experience, all working together to make compost with the rice husks and dry leaves and water. Seeing how folks from all different ages were learning about how compost works, the different uses for it and the benefits for the soil just highlighted the importance of learning exchanges to me.

We began the second day by separating the corn husks from their stalks and then putting them in bags. The men explained they had left aside a small part of the harvest, so we could see how it’s done. We then went to see a neighbor’s parcel tended by Doña Rosario, who uses the raised bed system as well. She showed off her large pig that recently gave birth to 5 piglets. She shared that one of her previous pigs had given birth to 19 piglets! We also visited the land of Don Bismarck’s brother, Antonio, where we saw how sugar cane and grass are used to feed the cows. We helped with the process of preparing the sugar cane and grass for animal feed, as well as helped the women dig holes around the trees and put bamboo around them to help with the hydration process. The best part of this experience was watching the students of the IALA (Latin American Institute for Agroecology) – who were also part of the delegation – teaching older campesinos (farmers) about methods to use on their land to help them with its care in order to build up the soil to make it richer for food production. By watching this inter-generational exchange of knowledge, I could see the full meaning of agroecology in action: nurturing and caring for the soil and the people. The respect I observed that the men hold for the women in the community is clear and shows how education and shared learning contributes to building solidarity. The rural women in Nicaragua demonstrated to me that they are determined to farm their land sustainably and to free themselves from depending on agribusiness. Learning about this community and the variety of foods they grow — from maize to beans, yucca, sorghum, sugar cane among other vegetables and staple crops — demonstrated that diversified production can benefit a family’s ability to feed itself and the entire community through the local markets where they sell the surplus and cash crops.

The Marlon Alvarado community exemplifies what it means to be autosostenible (self-sufficient) and food sovereign at the community level. What this community, like many others across Nicaragua, has learned has been paramount to survival and food security in the wake of the attempted and widely misrepresented coup that took place just a year ago, in April of 2018. The opposition, state security forces and pro-government armed forces set up roadblocks (tranques) along Nicaragua’s main roads and highways, which effectively paralyzed the country’s economy and prohibited the movement of people, so much so that people in the city could not get the goods and help they needed.

Despite the immobility and isolation these tranques resulted in, the women we visited told us they have everything they need to survive in their own backyards and rural communities. Due to agrarian reform and the support of the ATC, families have land, communities are organized and continuing to learn together. Farmers, and community leaders, and women in particular, are crucial to the food security and food sovereignty of Nicaraguan families.