In 1839, the U.S. government forced the ancestors of farmer Randy Woodley from their Cherokee land. Centuries later, white supremacists forced Randy and his family from that same soil. Now, Randy and his family are seeking reparations.

Reparations within the U.S. context represent any efforts to compensate individuals and communities systematically disenfranchised throughout history. When I asked Randy if he encounters misconceptions relating to reparations, he laughed and told me that “people have a hard time wrapping their heads around reparations because they don’t understand why they’re needed.” Just as owning land represents an American ideal, there also persists what Randy calls the “American Myth,” the belief that people always harbor the “ability to find a different reality than the one they have,” or easily surpass deliberate obstacles that are intended to oppress.

Historically, Americans have discussed and debated various modes of reparations, and today there is growing awareness of its objectives. Currently, the meaning of reparations takes many forms: direct financial payments to individuals and communities, community investment through public resources like schools, and as author and educator Ta-Nehisi Coates suggests, a national reckoning—one in which those who have flourished identify their success as the consequence of others’ oppression.

Some models call for tangible payments, while others center on a more conscious awakening. The Woodley Family is seeking reparations in the form of land. And they’re not alone.

Soul Fire Farm, a New York farm dedicated to ending racism and injustice in the food system, has created a Reparations Map to connect financial reparations to people of color in the United States who have been disenfranchised. This reparations model is specifically focused on remunerating those who are reclaiming U.S. land to grow nourishing food; from California to Connecticut, the Map features more than 50 organizations seeking reparations so that they can cultivate land–an entity that has been systematically stolen from specific communities.

Land and property ownership is a pillar of American achievement. Historically however, this acquisition has been made impossible for millions of people. From sharecropping to redlining, people of color have routinely been prevented from land ownership, or have had whatever land they owned stolen through legal loopholes or scare tactics.

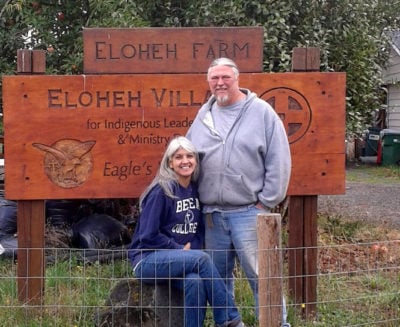

Woodley and his family built their Eloheh Village for Indigenous Leadership and Eloheh Farm on his people’s original homeland in Kentucky. They cultivated the land, harvesting crops and planting orchards. They constructed buildings, developed springs and cared for livestock. In 2006, the Woodleys started to experience violent pressure from a local white supremacist group to relocate. The Woodleys received no legal protection and lost everything. The village and farm were valued at over $350,000.

The Woodleys rebuilt Eloheh Village and Farm in Oregon in 2008 and developed a seed business as well. After ten years however, Randy who is also a professor has struggled to find employment and the high cost of living has forced the Woodleys to search for a new home.

When I spoke to Randy over the phone, he and members of his family were driving back to Oregon from New Mexico where they had been looking at new land. Randy said that the plot in New Mexico was not his native land, and while he and his family were welcomed there, he was “reconciling with feeling like a settler” himself.

Rebuilding a life is an expensive endeavor. The Woodleys are among other groups and organizations seeking funds through the Reparations Map to help them achieve their goals. One such group is Seed, Root + Bloom from Boston, Massachusetts. The group is dedicated to the study of herbalism within the teachings and traditions of Indigenous, Black People of Color, (IBPOC).

After participating in Soul Fire Farm’s Black-Latinx Farmers Immersion, Seed, Root + Bloom’s founder, bellx, started the organization with the intention of bringing knowledge about regenerative farming back to Boston. From zoning laws to underserved neighborhoods, bellx explained to me that the urban landscape hosts its own set of struggles. While only one year old, the small but quickly growing group is currently based out of bellx’s backyard in the neighborhood of Roxbury. Seed, Root + Bloom aims to expand their healing practices and educational capacity and occupy more vacant lots throughout the city, but the group is confronted by both financial and political barriers to accessing land—ones that they believe can be alleviated through their participation in the Map.

Jahshana Olivierre’s Soil & Soul Project is also featured on the Map and similarly faces a lack of access to green space in an urban setting. Jahshana, now 22 years old, witnessed the creation of the Map and established Soil & Soul when she was 19. She describes the organization as “a healing justice initiative” that nourishes the emotional, physical and spiritual wellness of youth through gardening and herbal restoration of the self. The organization is based in the Canarsie neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York.

Soil & Soul wants to expand their youth-and-elder programing and move away from the commodification of knowledge. Jahshana envisions a sharing of knowledge that allows for the reclaiming of all bodies within a community—not just those who can afford to pay. Like other organizations on the Map, she seeks monetary resources, but she is also looking for reparations in the form of knowledge and skills that don’t come with a price tag. To Jahshana, “reparations is a resistance towards capitalism…it’s disrupting that system.” She elaborated that “the nature of capitalism limits the possibility of projects.”

Soil & Soul wants to expand their youth-and-elder programing and move away from the commodification of knowledge. Jahshana envisions a sharing of knowledge that allows for the reclaiming of all bodies within a community—not just those who can afford to pay. Like other organizations on the Map, she seeks monetary resources, but she is also looking for reparations in the form of knowledge and skills that don’t come with a price tag. To Jahshana, “reparations is a resistance towards capitalism…it’s disrupting that system.” She elaborated that “the nature of capitalism limits the possibility of projects.”

At the end of our call, Jahshana said that “everything’s connected to land.” You can’t have a home without land, a neighborhood without land, a community without land. Despite bellx and Jahshana seeking green spaces in the city and Randy and his family looking for rural soil in the western United States, all of their organizations and livelihoods depend on their having access to the space and resources to continue their work.

At the time of publication, The Woodleys, Seed, Root + Bloom, and Soil & Soul had not yet received any funds through the Map. However, they are three examples of the power that Soul Fire Farm’s Reparations Map represents; the Map offers allies an opportunity to complete actions that have an immediate effect on individuals all around the country.

bellx stressed that reparations is not charity. Reparations means recognizing one’s own privilege as the result of someone else’s exploitation and demonstrating that recognition through actions, not just words. Reparations requires one to recognize their own benefit from and contribution to oppressive and historically violent systems.

Over the phone, Randy’s son Young added that despite their setbacks, his family will keep moving forward. “People endure,” Young said. “We become stronger.”

To support groups on the Map and their efforts to create a more just food system, you can find descriptions of each group and their requests here. If you would like to stand in solidarity with the organizations mentioned in this article, you can read more about their missions online: Eloheh Village for Indigenous Leadership and Eloheh Farm, Seed, Root + Bloom and Soil & Soul Project.

Audrey Fromson is a rising second year student at the University of Chicago. She was the summer 2018 Communications Intern at WhyHunger.