WhyHunger’s Director of the Nourish Network for the Right to Food, Jessica Powers, gave the keynote address at Hunger Action Network of New York State’s annual meeting on September 28th in Albany, New York. Here are her remarks.

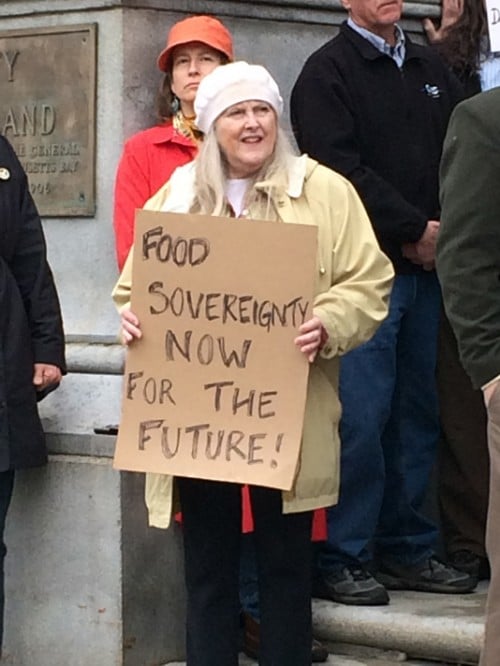

Maine is the first state to pass local ordinances in favor of food sovereignty, or the right of communities to determine how their food is grown, processed and distributed.

Maine is the first state to pass local ordinances in favor of food sovereignty, or the right of communities to determine how their food is grown, processed and distributed.

Not everyone is familiar with the term right to food. We’re used to hearing phrases such as “everyone deserves access to food” or “food is a basic human need.” But the term “right to food” strikes a deeper, more political chord that doesn’t often resonate with our traditional American view that feeding the poor as an act of charity or good will. However, more and more—especially over the last couple of years—we have been hearing a call for the “right to water”—from our partners and neighbors in Detroit, in Baltimore, and in California. Invoking the “right to water” is not a demand for a system where the government provides unlimited quantities of water to everyone. Rather, it calls for the government to ensure that management of water—which is our shared natural resource—is safe, fair, and sustainable. It’s not fair when businesses pollute water so that it can’t be used. It’s not fair when 90% of water resources around the world are controlled by private corporations. It’s not fair when an elderly person who owes a hundred dollars on a water bill in Detroit has her water shut off, but a privately held golf course owing tens of thousands of dollars continues to have access to water. So people have been coming together and asserting—demanding—their right to water.

The right to food is both a call to action and a global legal framework for coordinated reform in food and agriculture. In the US, we often speak of our civil and political rights, like the right to marriage or the right to be free from police harassment, but less often about our social, cultural, and economic rights, like the right to affordable housing or the right to a minimum basic income. Perhaps that is one reason why we see the worst income inequality and highest concentration of wealth in this country since the robber barons during the Great Depression.

There’s a saying that when we have programs for the poor they become poor programs. Nearly five decades of food banks have failed to solve the problem of hunger because it frames the problem as a lack of food (hunger), rather than a lack of income (poverty), and the solution as distribution, not structural change. With four out of five people in the US experiencing poverty at some point in their lifetimes, we need to talk about income inequality, living wage jobs, and the right to food as a shared struggle that impacts all of us. For me, I experienced poverty when I was a kid and my family was on food stamps and again during the years I worked in foodservice for low wages. For you, that might mean the years you served in AmeriCorps or when you were unemployed or had an accident or health issue. I’m sure I’m not the only person here who has a deep discomfort with anti-hunger organizations and funders who choose to focus solely on childhood or senior hunger as deserving of care. To focus on one demographic obscures the fact that we won’t solve hunger until we embrace the right to food for everyone. A human rights approach says that all people have value and it acknowledges history and structures that have left some people more vulnerable than others. When we talk about the right to food, we maintain that government has a role in protecting the most vulnerable, in preventing consolidation of power and control, and of ensuring that nutritious food is available in our communities at an affordable price.

Our band aid approach is not enough, and with four or five companies processing most of the grains, dairy, and meat in this country, we have failed miserably at regulation. The right to food and concept of food sovereignty say that producers and consumers of food—rather than corporations—have the right to determine what our food system looks like. The consequences of industrialized agriculture to our health, economy, and environment are shared by all of us. Industrialized agriculture uses 70% of agricultural resources to produce 30% of our food, while small scale production uses 30% of resources to produce 70% of our food. One out of six jobs in this country are in food or agriculture, and most of those jobs do not currently pay a living wage. Many are precarious jobs, meaning that they’re unsecure or contract or part-time, so people resort to cobbling together different jobs without benefits or protection. This is deliberate. We have moved from a food and agricultural system that was propped up by slave labor to one that is propped up by migrant labor and low wage jobs and we need to change that. Community food production and the breaking up of monopolies are important because when the motive of our food system is consolidation of wealth and unsustainable profit, we all have fewer choices. During World War II, there was promotion of Victory Gardens, home gardens to aid in food production and ensure food security. These gardens produced half of the US food supply. But you can’t monetize that. You can’t profit from community self-sufficiency. So the marketplace was ruthlessly consolidated. But consumerism and cheap calories also have consequences: environmental destruction, diet-related disease, less community, low wage jobs.

We have responsibilities as rights holders. We must organize, imagine, and plan together, hold government accountable, and be vigilant about maintaining our rights over time. We can learn from Brazil, Venezuela, and Bolivia—where social movements asserted the rights of people to natural resources. Venezuela saw a reduction of poverty by half in four years from 2003 to 2007, a 70% reduction of extreme poverty, and a 6% reduction in income inequality. (Compare that to a rise of 6.6% in the US.) This happened because people worked together and asserted their rights. A rights based framework necessarily demands racial and economic justice and wealth redistribution.

So how did the right to food come about? In his Four Freedoms speech, New Yorker Franklin Delano Roosevelt spoke of freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. Freedom of speech and worship were already protected in the US Constitution. By including freedom from want and freedom from fear, he was doing something truly radical, endorsing economic security and social rights, or what is now known as a “human security” paradigm. He was also acknowledging a tension between the American ideal and the reality; the rights expressed in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution on the one hand, and a history of slavery and racial discrimination on the other. The Four Freedoms were later incorporated into the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights by his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt.

The International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights went even further, asserting the “right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing, and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions” and “the fundamental right to freedom from hunger and malnutrition.” The US has signed but not ratified the Covenant. In Article 17 of the New York State Constitution describing social welfare, Section 1 says:

The aid, care, and support of the needy are public concerns and shall be provided by the state and by such of its subdivisions, and in such manner and by such means, as the legislature may from time to time determine.

Is the State of New York fulfilling its obligation to care for poor people when there is increasing income inequality and privatization of charity? When elected officials are increasingly part of an economic elite that overestimates how much money average people have, how can they make realistic decisions affecting the budgets of low and middle income people? In fact, New York county and Westchester county rank third and twenty first in the nation on the Gini index, a measure for income inequality. As a legal framework, the right to food does not claim that government is responsible to feed everyone, but rather, it asserts that government must put the structures in place that insure that everyone, particularly those most vulnerable—women, people of color, the elderly, children, the working poor, LGBT folks, people with disabilities, and precarious workers—have the resources to be able to acquire sufficient food with dignity.

What does the implementation of the right to food look like? In Brazil, through the Zero Hunger program, the government sought to address structural issues underlying hunger. The Zero Hunger program has provisions to create better income through job and income policies, agrarian reform, universal social security, school grants and minimum income, and microcredit. It also works to increase supply of basic food products through support to family farming, incentives and production for self-consumption, and agricultural policy. It creates cheaper, but healthy, food products through subsidized restaurants, agreements with supermarkets and grocery stores, alternative marketing channels, public facilities, a worker’s food program, anti-concentration laws, and cooperatives of consumers. And finally, through specific actions such as food stamps, disaster assistance, school meals, food security stockpiles, and actions against mother-child malnutrition. The Zero Hunger program attempts to address the host of structural issues that create food insecurity in the first place, like low wages and lack of income generation, high interest rates and agricultural crises. The Zero Hunger program came about because of the mobilization of people and civil society, including businesses interested in corporate social responsibility.

The right to food means that we should have access to food, that it is adequate, or nutritious and safe, available during disasters, and sourced and produced in sustainable ways. The role of government is to regulate the activities of corporations, to strengthen access to resources, and to implement effective social programs. Just like civil rights, gay rights, disability rights, prisoner rights, and others, the right to food is not solely about laws. It is about a broader vision of community self-determination and liberation. Our role is to organize. That is how we can change the story from one of hunger to one of rights.