‘Apple’ at the MoMA. Photo: New York Times

‘Apple’ at the MoMA. Photo: New York Times

It all starts with the apple. The glowing green fruit (surely a Granny Smith) sits on a clear plexi-glass plinth just inside the entrance to ‘One Woman Show’, a retrospective of the 1960-1971 work of Yoko Ono currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art.

Apple, of course, is not the original artwork. Like many of the pieces in the exhibition, it is a careful recreation of Ono’s ephemeral early work – an apple that decays and is replaced, a piece of canvas placed under a dripping water bottle and of course, Painting to be Stepped On, which lies on the floor, ready to tread.

Ono’s art lends itself uniquely well to this hybrid display of ‘original replicas’, since inviting reproduction is one of the hallmarks of Ono’s practice. In 1961, the artist had her first solo show at AG Gallery, an exhibition which introduced New York to Ono’s ‘instruction paintings’ – canvas cut-outs painted in Japanese ink, and accompanied by a description of how the painting was made and could be made again. For instance, for Smoke Painting:

“Light canvas or any finished painting with a cigarette for any length of time. See the smoke movement. The painting ends when the whole canvas or painting is gone.”

By 1962 Ono had done away with the paintings, and was exhibiting the instructions by themselves. In 1964, she self-published Grapefruit, a collection of her instruction pieces from 1913-64. The MoMA exhibition displays a 1963 typescript for Grapefruit, spread along the walls. Each page features a single set of instructions, all of which invite the viewer to take action – be it minute (“Draw a line. Erase the line.”), humorous (“Write all the things you want to do. Ask others to do them and sleep until they finish doing them. Sleep as long as you can.”), or metaphysically fantastic (“Listen to the sound of the earth turning.”)

In one of the museum’s accompanying audio recordings, Ono explains that using text to prompt creativity is an idea that goes back to her childhood. Growing up in Japan during World War II, Ono’s family was often hungry. One day, seeing her younger brother miserable with hunger, she entertained him by creating an imaginary menu for him – “I said, desserts can be ice cream!” Ono described how “fresh and beautiful” it was to see her brother rejuvenated, just by using his imagination. “This is it!” she remembered thinking. Art, and the imagination and creativity it fosters, could be more than visually pleasing – it could be spiritually nourishing.

This sensitive, open-ended approach to gesture shines through in Ono’s adult work – in her activism, as well as her art. Her 1966 White Chess Piece removes the color demarcations of the board and pieces. The seemingly small gesture transforms the militaristic game into one with no clear sides, in which players must work cooperatively, or not at all.

The Original Bed-In. Photo: MoMA website

The Original Bed-In. Photo: MoMA website

In a more public gesture asking for change, Ono and her new husband John Lennon transformed their 1969 honeymoon into a well-publicized anti-war protest. Clad in white pajamas, the newlyweds staged the weeklong Bed-In for Peace, opening their room to reporters, artists, and activists for 12 hours every day, to discuss the need for an end to war. In the accompanying audio recording, Ono chuckles at their optimism. “John and I thought, after Bed-In, the war is going to end. How naïve we were. The thing is, things take time. I think it’s going to happen. I think we’re going to have a peaceful world. It’s just going to take a little bit more time than we thought then.”

Ono and the ‘Imagine’ team, 2012

Ono and the ‘Imagine’ team, 2012

Ono’s memory of hunger remains, and her activism continues to be informed by it. Since 2008, she has partnered with WhyHunger and Hard Rock International for Imagine There’s No Hunger, a campaign that helps grassroots organizations develop sustainable agricultural solutions to local hunger in 20 countries. Imagine has helped communities grow enough food to provide families in need with an estimated 9.7 million meals, and has raised more than $6.4 million to nourish, educate and support children worldwide. And, true to both Ono and WhyHunger’s ethos, Imagine is a campaign that questions existing assumptions about hunger and charity, and has inspired has tens of thousands of supporters with the belief that the people who have the best understanding of a community’s needs are the people who live in it. At the 2013 WhyHunger Chapin Awards Dinner, where she received the ASCAP Harry Chapin Humanitarian Award, Ono remembered her struggle as a nine-year old child in wartime. The same little girl who drew a menu to cheer up her brother was determined to provide for her younger siblings, despite the limited resources. Ono would drag home sacks of potatoes, so heavy for her that she could only move a few steps at a time. “Let’s try so that one child will not be without food,” she asked the audience. “Because not having food is very hard, and I remember it.” The video of her speech can be watched here.

In support of Imagine, Yoko and WhyHunger partnered in 2013 to produce ‘John Lennon: The Bermuda Tapes’, an interactive app that integrates documentary storytelling and Lennon’s Bermuda demo tapes in an innovative game. The app gives offers unique insight into both Lennon and Ono’s art and music, and their shared vision of a better world.

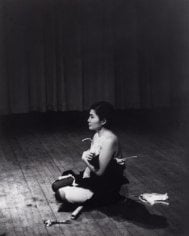

Ono’s ‘Cut Piece.’ Photo: Minoru Niizuma, Lenono Photo Archive

Ono’s ‘Cut Piece.’ Photo: Minoru Niizuma, Lenono Photo Archive

Ono and Lennon met at the 1966 London exhibition where Ono first installed Apple. Ono remembers that Lennon, who arrived at the gallery the day before the opening, walked in and took a bite of the apple, much to her outrage. (It seems worth noting that two years later, Lennon, with the other Beatles, would found the music label Apple Records, whose icon, a bright green apple, became famous in its own right. It’s this kind of circle of happenstance and poetry that Ono’s work invites you to consider. The storied life of an apple.)

‘One Woman Show’ ends on September 8th, and it’s certainly worth a visit. Yoko Ono’s early artwork, much like the woman herself, is not only legendary, but still relevant, hip and vital . In inviting you to perform simple actions, Ono challenges you to question the way you interact with the world, and gives you the opportunity to change it.