It was a Sunday morning and the idea was to visit the Itaparica Dam with my auntie Tania. Her husband, my uncle Fernando, worked as engineer for the government company that had built it. The dam was spectacular, a massive wall of concrete with a tower in the middle of it to control the flux of water. But there was a catch that took away from the splendor. That exact dam had displaced 70,000 families from their homes and farms. And according to my relatives, there were still families who haven’t received a single penny for being forcibly displaced by the dam twenty years later. I recall my mother shaking her head in disbelief. Indeed, twenty years is a long time.

What should have been only a fun afternoon turned into much more than a tourist visit, and that experience has served me well. It was moment of reflection and learning. As a teenager, still ignorant of the reasons for such things, I was challenged by my inability to conciliate such a beautiful landscape of a “small ocean” and the fact local people who had to move to make space for it didn’t have tap water in their own homes.

It was only later, when I was in college, that I learned that the families impacted by the Itaparica Dam weren’t just sitting around waiting for their checks on the mail. In 1991, along with families affected by other dams in the South of Brazil, they helped to create the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB). Their vision for MAB was to have a voice in national policies and create an organization that would defend their rights.

As a mass, social movement, MAB is currently represented in 17 states of Brazil, with an estimated membership of 60,000 people. MAB works on different intertwined fronts that include organizing; political education; legal support and alliance building. MAB has won important victories in recent years, such as:

•The publishing of the government-sponsored report on the human rights violations created by dams. In the launching of the report Lula da Silva, the country’s President at that time, spoke publicly about those violations, recognizing the social and economic debt of Brazil with the families. It was the first time a high rank government official had addressed those violations.

•The creation of the National Peasant and Workers Platform on Energy formed by families affected by dams and workers in the Energy sector.

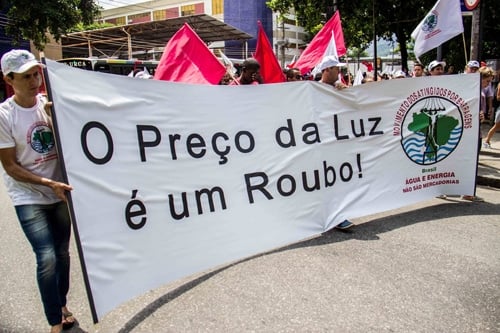

•The national campaign “The Price for Electricity is a Shame” helped to mobilize and educate thousands of low-income families for the fact that Brazil had one of the highest rate for Kilowatt even though most of its electricity originates from hydropower with the lowest production of energy.

But mostly important, MAB has become a source of inspiration for many families in Brazil and Latin America in general. Its sharp analysis summarized in the motto “Energy for What and for Whom?” addresses the views of indigenous people, low-income workers, environmentalists and scholars about the greed behind mass energy production and challenges the debate about fossil fuel vs. “clean energy”. MAB’s analysis goes beyond that and provokes us to answer the question: “whom controls the energy?”

In times when we are challenged by melting of glaciers, we have no other option to do our best to answer those questions that MAB raises. And today, March 14th, on the International Day of Struggle Against Dam, thousands of families affected by dams are organizing marches, workshops and other events. They are inviting us for a moment of reflection and action. It is imperative that we join them.

“Let’s say it together, with our hearts: No family without a home. No peasant without Land. No worker without rights. No one without the dignity that the labor gives.” – Pope Francis

Looking back on that Sunday morning, my mother’s reaction prompted me to reflect on the harsh reality of families being pushed out of the comfort of their land, without any support to start a new life. The energy produced by that dam offered little benefit to them, because their new homes had no connection to the electrical network. And, now far away from the river, they had to grow food based on the scarce rains in that the dry region of Northeast Brazil.

My continuous growth as a person relies on my capacity to think critically on the structural problems that affect not only my own life, but also the wellbeing of others. Reflecting on MAB’s questions and not staying on the sidelines, I can only find strength to keep asking new questions. If we are to produce energy from new sources – like solar panels and gigantic windmills, who should benefit from it? Does it respect the rights of Mother Earth, the breathing being that feeds all of us every day?