{loadmodule mod_rokgallery,afedes}

On my first day volunteering with WhyHunger partner AFEDES (Women’s Association for the Development of Sacatepéquez, Guatemala), I visited a community in San Antonio Aguas Calientes with self-proclaimed “agro-eco-feminist” Mercedes Monzón. Held at the home of one of AFEDES’s members, the meeting’s objective was to learn about the low-impact pesticide lime sulfur and to make a big batch for the group of 10 women to share. In one morning, these goals were met and more. We drank mosh (a sweet oat-based drink) followed by a savory atol (a warm corn-based drink) topped with beans and ground pumpkin seed. As we sipped and worked, group members also shared their frustrations and successes, whether it was a sickness affecting their hens or a bountiful harvest of medicinal plants from their herb garden. AFEDES meetings create these safe spaces for women to come together, to get away from their worries at home and to focus on improving their livelihoods.

Although many members of AFEDES have barely finished primary or secondary school, they keep attendance, minutes, financial records, and plan for their futures. Women in rural communities form organized groups and elect their own presidents, treasurers, and promoters, who become leaders, supporting their compañeras in anything from taking legal action against domestic violence to learning new weaving techniques. These groups later report to the general assembly at AFEDES, which also has its own leadership structure. This dynamic builds networks of solidarity among women within and across communities. I found this especially powerful in a world where women are taught to compete against each other rather than work together.

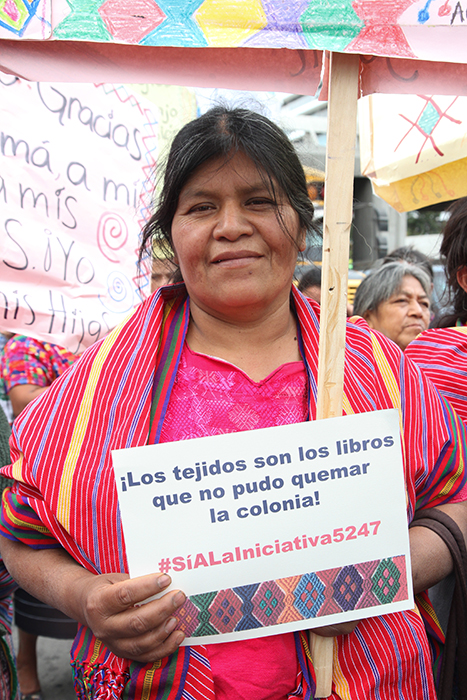

Olga Zet, vice president of AFEDES, shows support for the Weaver’s Movement.

After wrapping up in San Antonio, we headed to Santiago Sacatepéquez, home of AFEDES headquarters, where we found the office staff in a workshop on bio-energy. I certainly did not expect to receive a chiropractic adjustment on my first day as a volunteer, but I happily obliged after a two-day bus journey through the mountains of Chiapas and Guatemala. After our adjustments, a naturopath led us through a series of energy-balancing processes to center our minds and bodies. Even though I had quite literally just met everyone in the room, I felt a certain unity and connection as we flowed through the different energy centers of our bodies.

Milvian Aspuac, director of AFEDES, later explained to me that workshops like this are part of the holistic approach the organization takes towards building autonomy among indigenous women and their communities. This vision of autonomy includes physical, political, and economic facets of life. For example, reclaiming women’s health, both physically and spiritually, is one of the important pillars of physical autonomy. AFEDES is also guided by the principle of Utz’ K’aslemal, their response as Kaqchikel women to “buen vivir” policies in countries like Bolivia and Ecuador. The ultimate mission is to defend life itself.

Milvian pointed to a large wasps’ nest outside her office window. “We don’t kill these wasps because they are life,” she explained. When there is a march to defend water, AFEDES will be there because water is life. When communities organize against a mining project, AFEDES will be there because land is life. This political clarity is a result of over 20 years of organizing, during which AFEDES has seen many changes in its vision and mission. Through a restructuring process in 2012, the women focused on their core values by asking themselves, “What do we really want?” The answer wasn’t more money or more things, but simply to live well, vivir bien, Utz’ K’aslemal.

With this perspective, elements that might seem disconnected at first soon become inseparable. My first week with AFEDES, I attended a harvest festival and ceremony in the mountains of Chimaltenango and the next day I joined the National Weavers’ Movement in the capitol presenting legal reforms to protect indigenous textile designs (their proposal was accepted in February and is now awaiting approval from the Commission of Indigenous Peoples). Through these experiences, I saw first-hand how women and their communities are organizing and building resilience from the ground up. It’s all part of defending the web of life.

Weaving class at AFEDES headquarters in Santiago Sacatepéquez.

I arrived at AFEDES with an interest in gender and food sovereignty, which began with learning to grow my own vegetables in my mom’s garden and led me to study Human Ecology with a focus in sustainable food systems at College of the Atlantic in Maine. I was especially drawn to AFEDES’s focus on gender and racism in addressing problems in the food system, as a revolution without intersectionality is no revolution at all. What I gained over the six weeks I spent immersed in this community was more than I could have hoped for: I left with a much more complete vision of the kind of world I want to live in and the steps I can take to make that a reality.

As I watched from afar the social movements making waves back home in the U.S., from a pipeline resistance in my home state of New Jersey, to dairy workers organizing for better protections and wages in Vermont, I began to see them all connected in the bigger fight to defend life itself. On many occasions I asked myself, “What would my Utz’ K’aslemal look like without the confines and pressures of capitalism, patriarchy, and racism? What does autonomy mean to me?” I certainly don’t have all the answers, but I think I am beginning to ask the right questions.