In the next issue of the Nourishing Change newsletter, we focused on discussing the importance of narrative change in the food system. To do that, we spoke with two of our partners, food justice organizer Shane Bernado and Kristen Kozlowski of Bread for the City, about how we can highlight the true solutions to ending hunger. Read below and let us know if you have other ideas about how we can work to change the narrative around hunger.

A Conversation with Shane Bernardo, storyteller, healing practitioner and food justice organizer

- Why is narrative change work important to the struggle for justice?

I once heard Christine Codero, Executive Director of the Center for Story-Based Strategy say at one of their narrative change trainings, “we are narrative beings.” We view and interpret the world through the stories of our lived experiences and those that are crafted by dominant power structures that shape our worldviews. If we are to create a more just world, a necessary part of that work includes changing the stories that are told as well as who is telling those stories.

Stories are powerful. While we may not be able to retain all the nuances and details of every story we’ve been told, the emotional impact of them stays with us forever. Stories have the power to heal us as well as normalize our oppression. When we create new narratives where we are agents of change versus passive participants, we also change the power dynamic needed to create the change we ultimately want to see. Quite literally, we speak ourselves and a more just world into existence.

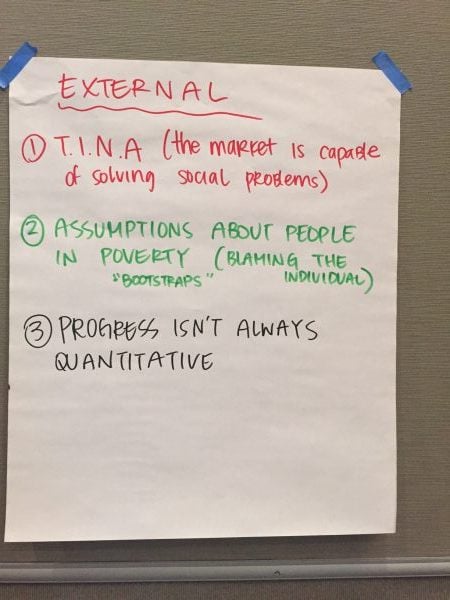

- What’s the current story being told, or what is dominant narrative? What’s the result of perpetuating that narrative?

The current narrative being told is that the system is fine and that we just need to make it more efficient and that people need to give more money. So the system works on the sympathy of other people and in some cases maybe it’s that there isn’t anything that we can do about it, that we’ll always have people in poverty. There’s no long term solution and charity is the primary model for alleviating poverty. The narrative is very much based on either missionary or savior approach. The people that are in poverty are always going to be the perpetual victims that play a tacit role in the whole equation around poverty.

People are not hungry or poor because of lack of access to food or economic opportunities. People are poor or hungry because of the disparities around power. So part of the solution is changing or dismantling inequitable power structures, so the people suffering from chronic poverty and chronic hunger are placed in the driver seat. Those that are in a place in chronic hunger or chronic poverty know these issues most intimately and so part of the work is understanding is that they’re already part of the work because they’re struggling day to day, trying to make a way out of no way and doing the very best that they can with the least amount of resources. What needs to happens is that those of us that have institutional privilege and power and resources need to shift those things to where the greatest need is. We need to change the way that we think of our own positionality as it relates to institutional privilege and resources and how they can be redirected and facilitated to create the greatest change and make the biggest impact.

- What are ways that food access organizations can lift up the true solutions or tell the stories that highlight the true solutions?

Placing people that have been historically and systemically marginalized by structures of power in a place where they have the most agency around changing and dismantling those systems. By telling their own stories and doing it from a non-passive voice, so that we’re literally changing the power dynamics at play that continue to victimize people in chronic poverty and hunger. That in itself as a practice is a huge thing on the way to creating systemic change; telling our own stories. So in other words, when we tell our own stories, we’re able to write our own selves in as victors of those stories versus being victims.

A Conversation with Kristen Kozlowski, Associate Director of Development, at Bread for the City in Washington, DC

- What are the stories you believe are important to tell that highlight the “true solutions” to ending hunger?

It’s important to recognize that hunger is complex, especially in the United States where the problem isn’t always lack of food, but instead of lack of affordable and nutritious food. The agriculture industry is being transformed by innovation. This means efficient, cost effective food production. But innovation is not responsive to the needs of people that have low incomes, and who live in food deserts. The challenge of capitalism is that opportunities make their way to those with the most resources: fresh foods and ones that aren’t processed are too expensive for our clients, and groceries stores are seldom operated in communities where people with low incomes live. At Bread for the City, our job is to serve people in communities that aren’t favored in that way. We are the counterpart of this model.

It’s also important to share stories that reflect the fact that food insecurity impacts people of color in such a disproportional way. The lack of dollars, the income disparity for this community, is getting worse. The trajectory isn’t looking much better, but it is a call to action for many of us in the nonprofit sector. As a service provider, we have to think how to reform our own programs to be more responsive to this adverse path.

A “true solution” to ending hunger is going to have to engage with the history of racism in America and with the reality of the extreme income inequality we are experiencing as a society.

- What are one or two examples of stories you tell that shape the narrative of how to end hunger?

Bread for the City’s Holiday Helpings campaign is a yearly tradition in which we raise enough money to ensure that ~8,000 DC families have a turkey dinner for Thanksgiving or Christmas. Not only is Holiday Helpings valuable to our food program as a fundraising effort, but it connects our larger community through storytelling – like the client who reflects on only getting a Thanksgiving dinner as a child because of Bread for the City, or the former client who now donates to the campaign because we were there for him when he needed some extra support. The holidays are really a time where everyone in our community is reflecting on their lives. Holiday Helpings connects people through storytelling in a way we don’t see very often: across socioeconomic, race/ethnicity, and other lines, everyone loves to share stories of their own family traditions.

- What is the value of storytelling to the work you do?

Storytelling is intrinsic to Bread for the City’s mission to support our clients and their communities in developing and exercising their own power to make change. Storytelling is powerful because it focuses attention where it should be: on the people most impacted by structural inequalities such as hunger.