Written by Elena Seeley

Growing up, my understanding of May Day in this country hardly extended beyond Maypoles and flowers. Though I knew that somehow, somewhere the labor movement was implicated, I never learned that May Day commemorated the establishment of the 8-hour workday. And I certainly was never taught that the suppression of May Day’s history was deliberate. But outside of the U.S., May Day, or International Workers Day, is recognized as a holiday in dozens of countries. It is a celebration of the solidarity of workers, their labor, and efforts to build economic justice around the world.

While May Day can be traced back thousands of years to ancient celebrations of springtime and fertility, documented worker protests first occurred on this date in the late 19th century. During this time, workers still toiled for 10- to 16-hour days in harsh environments. In the 1880s, this began to change through the work of socialist, anarchist, and cooperative movements. Fighting for better conditions, many unions sought to shorten the workday to 8 hours without a reduction in pay.

Among these groups was the Knights of Labor (KOL). One of the first prominent unions to integrate Black and white workers, it was, at its peak, the largest labor organization in the world. In her book, Collective Courage* Jessica Gordon Nembhard explains the KOL not only fought for an 8 hour workday; they also engaged in strong support of cooperatives.

Defined by the International Cooperative Alliance as “people-centred enterprises owned, controlled and run by and for the members to realise their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations,” cooperatives, or coops, are based on the pooling of resources and democratic economic participation. They have provided healthcare, food, and economic opportunities – everything that marginalized groups, including many Black communities, lacked adequate access to because they were systematically excluded from mainstream economies. These coops existed apart from a traditional capitalist system that is dependent on worker exploitation and allowed workers to claim their own labor.

In addition to this rise in coops, socialist groups, including political parties and labor unions, also began to emerge throughout the country. Many were initially drawn to the notion of controlling their means of production, but over time, thousands began to break away, frustrated by bureaucracy’s prioritization of government and large businesses. Although the unions continued to fight for workers’ rights, many did so within a new framework. Aligning with ideals of anarchism, they emphasized a worker-controlled industry and a country controlled directly by decisions of the people rather than representatives.

In 1877, labor movements built momentum as railroad workers from St. Louis to Pittsburgh went on strike for better working conditions. For a short time, it appeared the workers might be successful until President Hayes ordered the army to extinguish the protests. But, even while these efforts failed, the workers’ hope was carried into the next decade as the KOL continued to organize across the country.

In 1884 the Federation of Organized Trade and Labor Unions (later the American Federation of Labor) convened in Chicago and declared that May 1, 1886 would mark the beginning of the 8 hour work day. Radicals and anarchists initially expressed resistance to this approach, concerned it favored reform over the building of a new economic system. Nevertheless, thousands around Chicago, including the KOL, organized to support the idea of a shortened workday. As more workers joined the cause, radicals ultimately yielded and contributed their support as well.

But on the morning of May 1, 1886, many business owners refused to respect the new workday structure and over 300,000 people from 13,000 businesses went on strike across the country. In Chicago alone, the number of peaceful protesters rose from 40,000 to 100,000 over two days. Then, on May 3rd, tensions gave way to violence as police harassed and beat picketers, killing at least two and wounding many others. Anarchists responded with a call for a meeting in Haymarket Square on May 4, but as that night drew to a close, detectives who were present agitated the crowd. Though to this day nobody knows who was responsible, a bomb was thrown amongst those who remained, provoking police to fire their weapons. By the end of what came to be known as the Haymarket Affair, over half a dozen were dead.

The next day, martial law was enacted not just in Chicago, but across the country and anti-labor governments used the Haymarket Affair to suppress further labor movements. As police rounded up and convicted 8 suspected anarchists, the country came to associate anarchism with violence, and socialism with un-American beliefs. The event also marked the beginning of the KOL’s decline as the public linked the union to the bombing. As a result, the support of coops also suffered as wholesalers, railroad companies, manufacturers and more refused to work with them, inhibiting their ability to thrive. Within several years, most coops were forced to close or move underground before they could resurface in new ways.

In the years that followed, U.S. Presidents took further steps to dissociate May Day from workers’ rights. Fearful that the commemoration of the Haymarket Affair would build support for radical causes, President Cleveland first established Labor Day as a national holiday in 1894. Then, during the McCarthy Era of the 1950s, President Eisenhower created “Loyalty Day” on May 1st. Said to be a “reaffirmation of loyalty to the United States,” it was designed to mask any sort of connection to the workers of the world. Even as recently as the 1980s, President Reagan proclaimed May 1st to be “Law Day.”

As a result of these actions and the celebration of the more moderate Labor Day, the true origins of May Day has been largely erased from the public memory in the U.S. Many never learn about the struggle behind the 8 hour work day. They do not know that the day celebrates solidarity amongst workers of different races, classes, and backgrounds. And they do not realize that these values lay an important foundation for achieving class consciousness and ultimately, economic justice.

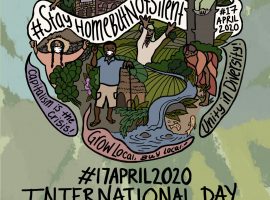

But the significance of May Day has not been forgotten. Around the world, dozens of countries have taken it up as a national holiday to honor international workers. As Nils McCune, PhD of the Rural Workers Association – ATC Nicaragua and 2019 Jo’ Ja’ Jcuxlejaltic Research Fellow explains, May Day in Latin America “is a sacred day when we remember the Cause — the struggle for freedom, for revolution, for a different society. May 1st is about the Power of the People. It is the day of greatest unity. Uncovering [its] history and recovering it, making it ours again, is surely part of what it means to lose our chains.” This is why it is important to reflect on workers’ struggles and their power, both abroad and here in the U.S.

Acknowledging this country’s history of divisiveness, it is possible to better understand the ways that economic justice is intrinsically tied to racial justice, immigration reform, and the right to food. At these intersections it becomes clear that race was constructed as a tool intended to disrupt solidarity along class lines. When landowners were able to convince poor whites that their skin color made them superior to enslaved Black men and women, they were able to distract them from the power held by the wealthy few.

To this day this strategy continues to be employed, the rhetoric evolving to serve the needs of those in power. It is apparent in the oppression of different racial and ethnic groups across the U.S., including immigrants, whose rights come second to the rights of the white working-classBut ultimately this racism serves as a barrier preventing all working-class people from coming together.

So as we look back to the Black coops that proliferated during the Great Depression and again during the civil rights movement, we see the power they held. We see how groups persisted despite threats to their homes, their freedom and their lives. We can see how they continued, and still continue, to challenge an economic structure designed to benefit white, wealthy business owners who depended on the exploitation of workers. And what is more, we see that, as these coops farmed the land that provided economic opportunity, they were able to supply the very food that sustains them.

Today, the movement continues through the work of a growing number of coops, organizations, and coalitions. From the Poor People’s Campaign to the Food Chain Workers Alliance, from the National Black Food and Justice Alliance to the community-based work of Elijah’s Promise, these groups are working to reclaim power and dignity for workers. Over the next several weeks, in honor of May Day, WhyHunger will be hearing from these organizations to understand what economic justice looks like in the food system and beyond. Through their stories we will try to disentangle and understand the many challenges that comprise this struggle so that we can dismantle these systems of of injustice and replace it with a new, equitable vision of a freed and self-sufficient people.

Born and raised in New York, Elena writes and thinks about about local, national, and global foodscapes and is pursuing an MA in Food Studies.

*Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s goes into some detail of the coop movement in her interview with Laura Flanders and a full explanation of the KOL and the labor movement of coops can be found in her book, Collective Courage.

Other Resources:

May Day’s Radical History:What Occupy Is Fighting For This May 1st

The Bloody Story of How May Day Became a Holiday for Workers

A History: The Construction of Race and Racism

How American Oligarchs Created The Concept of Race to Divide and Conquer The Poor